How a Mother’s Diet Changes Breast Milk: The Hidden Impact of PUFAs on Infant Health

How high-PUFA diets are changing breast milk, and rewiring the biology of the next generation.

The consequences of high‑PUFA diets don’t end with us. They’re rewriting the biology of our children from day one.

Breast milk, a sacred standard of newborn nutrition, has undergone a drastic transformation over the past century: and not for the better.

Breast milk now contains more PUFAs than ever before, because the types of fat you eat impacts the types of fat inside of you, which includes the types of fat in breast milk!

Prefer to listen? We’ve covered this in a two‑part podcast series exploring how dietary PUFAs are reshaping the fatty acid composition of breast milk, and why that change may be harming the health of the next generation. Tune in [Pt 1 here] and [Pt 2 here].

The Radical Shift in Breast Milk Composition

Historically, linoleic acid (LA), the primary omega‑6 fat found in industrial seed oils, made up only about 5% of the fat in human milk. Today, that number ranges from 15% to 25% (r,r,r).

This shift directly reflects modern maternal diets rich in PUFAs and more unsaturated fat stored in body tissues over time.

Why is that? Because the fatty acid composition of breast milk doesn’t just reflect what you eat today, it also draws from the fats stored in your body (r). In other words, years of dietary choices influence the very first food your baby consumes.

Why Does This Matter?

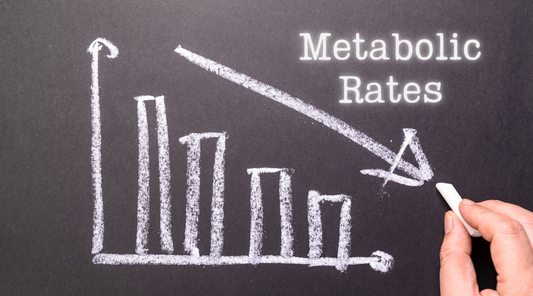

Breast milk is an infant’s first exposure to dietary fats: a powerful early imprint on their metabolic programming and fatty acid makeup.

Your internal fatty acid composition impacts your metabolism and how your body functions.

And research makes it clear: this rise in linoleic acid is not benign. Infants consuming breast milk with higher LA levels are being exposed to the harmful effects of polyunsaturated fats at the most vulnerable stages of development.

Where Do The Fats in Breast Milk Come From?

Breast milk contains all three macronutrients: carbs, fat and protein.

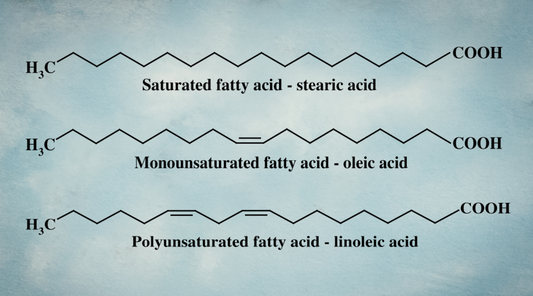

But the types of fat (total amount of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat) can change.

Both body fat composition and maternal diet influence the fatty acid profile of breast milk.

About 30% of breast milk linoleic acid comes directly from diet, while 70% originates from maternal fat stores.

“The data indicate that about 30% of milk linoleic acid is derived directly from dietary intake, whereas about 70% originates from maternal body fat stores.” (r)

Body fat stores of the mother plays a larger role in determining breast milk fatty acid content when the mother is not consuming sufficient calories while breastfeeding.

However, when calorie intake for the mother is low during breastfeeding, body fat stores play a larger role in determining breast milk composition.

Still, maternal diet has the greatest overall influence (r, r).

“In agreement with previous workers (5, 6) the data indicate clearly that dietary fatty acids are readily transported into milk fat.” (r)

And the more PUFA a mother consumes, the more PUFA ends up in her milk, while levels of protective saturated fats drop (r,r,r,r,r,r,r,r).

On the flip side, a higher dietary saturated fat percentage reduces PUFA levels in breast milk (r).

For example:

-

Adding corn oil (high in LA) to maternal diets increased LA levels in breast milk by 43% (r).

-

Consuming dairy fat, rich in saturated fatty acids, boosted SFA levels in milk (r,r).

In a human controlled study from 1985, mothers were fed controlled diets of varying polyunsaturated to saturated ratios. (r) Higher P/S ratios (more PUFAs, accomplished by swapping dairy fat with vegetable oils) led to more PUFAs and less saturated fat in the breast milk relative to lower P/S ratios (more dietary saturated fat).

“The composition of the fatty acids in breast milk was significantly different in the experimental group as soon as three days after delivery.”

Even low‑fat diets have been shown to increase the saturated fat content of breast milk (r), reflecting the body’s prioritization of these essential fats during lactation.

C15:0: An Overlooked Fatty Acid with Big Benefits

One fatty acid worth special mention is C15:0, an odd‑chain saturated fat recently recognized as essential and linked to numerous health benefits.

Found in full‑fat dairy, C15:0 appears in breast milk when mothers consume dairy fat (r).

In fact:

“Greater adherence to a ‘cheese’ consumption pattern during pregnancy was consistently associated with higher C15:0 levels in maternal and cord RBC membranes.” (r)

C15:0 has been tied to better cognitive outcomes and a reduced risk of metabolic diseases in early life, though research is still emerging.

Why the Fatty Acid Shift Matters for Infants

The research is clear: maternal diet profoundly impacts breast milk composition. And the implications are staggering.

“To conclude… we found that greater dairy fat intake could be associated with lower LA levels in breast milk. As lower LA level in breast milk was associated with better cognitive outcomes in the breastfed offspring.” (r)

Changing breast milk’s fatty acid profile away from historical norms can have lasting negative effects on child development.

Increased LA in maternal diets (and thus in breast milk) has been linked to:

-

Delayed psychomotor and mental development in infants as early as six months (r)

-

Lower verbal IQ scores (r) and reduced cognitive performance (r,r), with some studies showing effects persisting into adolescence (r)

-

Hindered immune system development, leaving infants more vulnerable to allergies and infections (r,r,r,r)

A fascinating study of farming families (r) found that children of mothers who consumed diets higher in saturated fat (butter, milk, animal fats) were eight times less likely to develop allergies compared to those whose mothers ate margarine and oils.

Notably, the farming mothers’ breast milk contained more saturated fat and less PUFA.

PUFAs, Oxidation, and Neurodevelopment

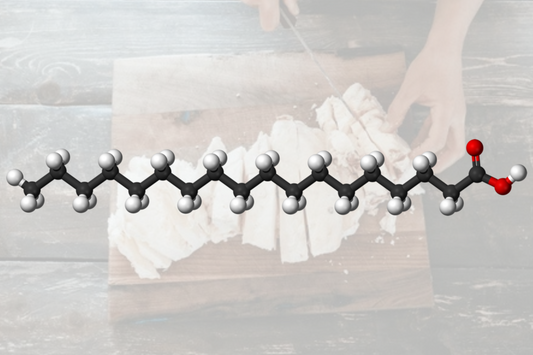

When linoleic acid oxidizes, it forms harmful byproducts called lipid peroxides, which degrade into biologically active toxic compounds like HODEs (9‑HODE, 13‑HODE). These compounds promote inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular damage, and have been tied to tumor formation and chronic diseases.

The consequences extend to neurodevelopment, too.

A study identified PUFA breakdown byproducts (diHETrEs) in umbilical cord blood, which were strongly associated with autism symptom severity in children (r).

“[H]igh levels of AA-derived diols in cord blood, including total diHETrE, 11,12-diHETrE, and 14,15-diHETrE, were found to impact ASD symptom severity significantly.” (r)

In other words, the waste products created when our bodies process PUFAs may be negatively impacting the neurodevelopment of children, even before they're born.

Other studies have linked high maternal omega‑6 intake to increased ADHD symptoms in children (r,r).

These findings fit into the fetal origins of disease theory: nutrition during pregnancy shapes the lifelong health and development of a child’s brain and body (r).

“The developing CNS is particularly vulnerable during intrauterine development to metabolic compromise… disruption of these processes by environmental factors will likely provoke long‑lived modifications to brain structure and, ultimately, function.”

And it doesn’t stop at the child’s brain development. Maternal intake of LA has also been linked to increased risk of mammary tumors. (r,r)

One study found that mice fed 20% corn oil had 1100% more 9‑HODE and 200% more 13‑HODE in mammary tissue compared to those fed 20% tallow (a saturated fat) (r).

The rise in autism and ADHD rates is likely multifactorial, but in the face of these growing neurodevelopmental disorders, every potential contributor deserves careful consideration.

The link between PUFAs and disrupted development may be a crucial piece of the puzzle, one that opens new avenues for prevention and intervention.

Here’s the Good News

This information may sound alarming, but it’s also empowering.

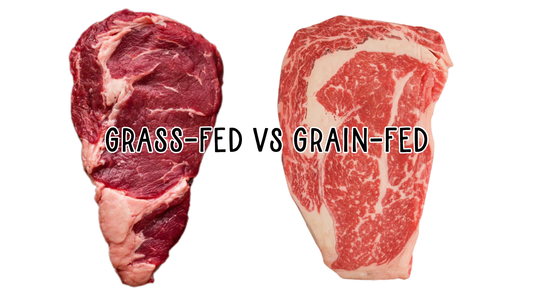

Dietary changes can quickly alter breast milk composition (r,r,r).

By prioritizing whole‑food sources and reducing PUFA‑rich oils, PUFA-rich conventional pork and chicken, and processed foods, mothers can shift breast milk toward a more protective, historically aligned profile, benefiting both their own health and their baby’s.

Ultimately, our dietary choices profoundly shape not just our health, but the health of future generations.

And while that carries weight, it also offers hope: we have the power to create positive change, starting with what we put on our plates.

Nourish Food Club:

At Nourish, we don’t just care about what’s on your plate, we care about the entire process that gets it there.

Our chickens, pigs, and goats are fed a custom, low-PUFA, nutrient-rich ancestral diet that I spent years formulating, designed to support metabolic health and produce meat, eggs, and dairy that are higher in stearic acid and saturated fats, and lower in harmful unsaturated fats.

Just like our great-great grandparents enjoyed, and drastically different from what’s widely available today.

Our goal isn’t to eliminate every trace of PUFA, as that’s not realistic (or needed). But we can restore a healthier fat balance that mimics how food used to be.

This is food as it was meant to be, before industrial ag PUFA’d everything.