Is Flour Bad for You? The Truth About Modern, Processed Wheat

You hear it everywhere today: “bread is bad,” “flour is unhealthy,” “gluten is toxic.” And now every recipe on the internet seems to be flour-free or gluten-free.

Okay… but what type of flour are we talking about? What kind of bread are we really eating?

Because not all flour (or bread) is created equal. Heritage flour and ancient grains are often much easier to digest and a superior product!

What most people don’t realize is that bread has been a dietary staple for thousands of years. It nourished ancient civilizations and remains the foundation of countless culinary traditions around the world.

Today, however, bread has a very different reputation. Once considered a fundamental food, it is now often avoided and can contribute to a range of health issues from bloating and brain fog to more serious conditions like celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

The reality: our ancestors thrived on flour and bread for thousands of years.

Now: it can make people sick.

So… what changed?

Modern flour can be:

- Genetically modified or heavily altered

- Coated with pesticides

- Baked with seed oils and additives

- Stripped of natural nutrients during harsh industrial milling

- Bleached and bromated for appearance and texture (exposing us to more toxic chemicals)

- Fortified with iron shards and synthetic folic acid

(Note: there are cleaner options for modern wheat that don't have all these characteristics, but the majority do).

Today, celiac disease affects approximately 1 in 100 people, with even higher rates of general gluten sensitivity. Yet just a century ago, these conditions were exceedingly rare.

Why would your great grandparents digest bread with ease while modern populations struggle?

The problem isn’t wheat itself: it’s what we’ve done to it.

Now, I am not saying you have to eat bread. But it isn’t something we should fear.

Bread and wheat are naturally rich in B vitamins, minerals like manganese, and polyphenols, and when properly prepared and made from clean, traditional grains they are a great healthy carbohydrate source (meaning, a great energy source!).

We see it time and again with our customers: once they switch to old-fashioned, chemical-free flour and traditional sourdough preparations, they can enjoy bread again without the issues that come from highly processed modern flour.

These are two entirely different products and lumping them together only creates confusion.

Let’s dive in!

Ancient Civilizations: Grain Becomes the Foundation of Life

Bread is one of the oldest foods on Earth: older than farming, older than most civilizations, and deeply woven into human history.

Archaeologists have found evidence that thousands of years ago people were grinding wild grains and baking early forms of flatbread, well before agriculture was even established. (ref)

These breads were simple: crushed grains, water, and heat. No additives. No chemicals. No industrial processing.

The Egyptians, for example, played a pivotal role in the evolution of bread-making. They discovered leavened bread when wild yeasts naturally fermented dough left exposed to the elements. This discovery revolutionized human nutrition and led to sourdough fermentation becoming the dominant bread-making method across cultures.

As farming developed, cultures like the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans began cultivating and harvesting ancient and heritage grain varieties.

Bread even shaped human settlements: early farming communities formed largely because people needed a stable place to grow grain for bread.

In ancient Egypt, bread was so essential that it was used as currency. Workers were often paid in bread and beer, and ration records functioned much like a paycheck system. Bread was a daily staple for everyone: from laborers to the wealthy, and it played a key role in community and culture.

"Bread is not only one of the oldest food staples in many cultures, but it is also a good marker of civilization. It’s present in some way or another in many ancient civilizations.

Bread helped to properly use the nutrients of the grains (through fermentation), and allowed them to use the stored grains during long winters. It built communities, brought people together, and shaped the routine of those who needed to bake bread every day.

In ancient Egypt, bread was one of the most important food staples; it was eaten daily by both rich people and the lower classes. We know some of this everyday routine of the ancient Egyptians because we’ve found drawings depicting its production” (ref)

The court bakery of Ramesses III. "Various forms of bread, including loaves shaped like animals, are shown. From the tomb of Ramesses III in the Valley of the Kings, Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt."

They stone-milled their grains, baked fresh daily, and relied on bread as a staple source of:

- energy

- minerals

- fiber

- B vitamins

Stone milling, the traditional method of grinding grains between two large stones, helped preserve the grain’s natural nutrients, oils, and flavor, which are often lost in modern industrial milling.

Because the grain was freshly milled and unaltered, their bread was nutrient-dense and deeply nourishing.

Image from (ref)

Traditional Food Culture

From medieval Europe to early America, bread was still made from:

- heritage grains

- stone-ground flour

- slow sourdough fermentation

- no chemicals

Bread has been at the heart of traditional food cultures around the world for generations.

More than just sustenance, it served as a symbol of community, hospitality, and ritual. “Breaking bread” wasn’t just a saying; sharing bread was a sacred act, symbolizing peace, hospitality, and alliance in many ancient cultures.

From the leavened loaves of Europe to the flatbreads of the Middle East, bread has shaped the way people gather, eat, and celebrate. Its preparation often reflects local ingredients, climate, and history, making it both a practical and cultural cornerstone.

In Italy, for example, the art of bread-making is woven into regional identity. In the north, ciabatta loaves with an airy interior and chewy crust reflects the heartiness of northern cuisine. In the south, traditional pane di Altamura from Puglia is celebrated for its golden crust, rich flavor, and long fermentation, earning recognition as one of the world’s finest ancient-grain breads. Both styles highlight how deeply Italian bread is shaped by local ingredients, climate, and centuries-old tradition.

Across the Middle East, flatbreads like pita and lavash are essential to daily life. Pita, with its characteristic pocket, accompanies everything from hummus to grilled meats, while lavash, thin and pliable, can serve as both plate and utensil. These breads are often baked in communal ovens, reinforcing social bonds and shared heritage.

In Western Europe, countries like France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands have also made bread central to their culinary identity. In France, baguettes are more than food, they’re a daily ritual, bought fresh each morning from local boulangeries and enjoyed with cheese, charcuterie, or butter. Switzerland is known for dense, hearty breads like Zopf, a braided loaf traditionally eaten on Sundays and holidays, reflecting both family traditions and regional pride. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, rye and whole-grain breads accompany every meal, forming a cornerstone of Dutch home cooking.

Even in Northern and Eastern Europe, bread remains deeply symbolic. In Russia and Poland, rye breads like Borodinsky or traditional sourdough loaves are served during holidays and family gatherings, often accompanied by hearty stews or cheeses.

These breads are not just food, they connect us to ancestry, local traditions, and the seasonal rhythm of life. Across the globe, it’s clear: bread is more than nourishment; it’s culture, history, and a daily ritual that continues to bring people together.

But most modern bread in America looks nothing like these traditional recipes.

Cheap and Abundant

Leave it to American industrialization to take a beautifully simple, traditional food and transform it beyond recognition. Bread and flour were mass-produced, and conventional agriculture shifted toward making them as cheap and abundant as possible.

In that process, we lost the very cultural practices that made bread nourishing in the first place: slow fermentation, careful milling, minimal ingredients, and high-quality grains. These steps take more time and cost more money, but they produce a far superior, more digestible final product.

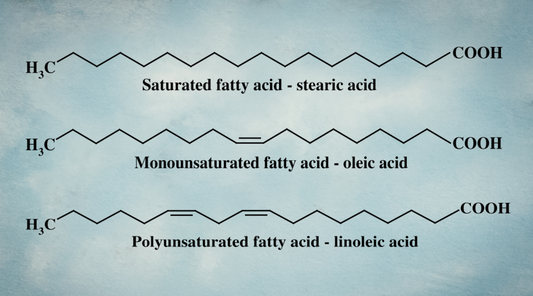

This shift began in the late 1800s with the rise of industrial roller milling. For thousands of years, flour had been stone-milled, preserving the bran, germ, and endosperm together, which ensured better nutrition, flavor, and digestibility.

Around 1900, steel roller mills swept across Europe and the U.S., replacing stone milling almost entirely. Roller mills stripped away the nutrient-dense bran and germ to create ultra-white flour with a long shelf life: perfect for cheap food and mass production, but low nutritional content. By the early 20th century, industrial white flour had become the default in America, laying the foundation for the modern, highly processed flour system we see today.

The Fortification Era

Walk down any bread aisle in America and you'll see the word "enriched flour" prominently displayed in the ingredient lists on nearly every package. This seemingly positive term masks a concerning reality: most modern flour has been stripped of its natural nutrients during processing, then artificially "enriched" (aka fortified) with synthetic versions.

Flour fortification began in the early 1900s as a response to the nutrient losses caused by modern industrial milling. Traditional stone-milled flour retained most of the grain’s vitamins and minerals, but roller-milled, heavily processed flour stripped away much of this natural nutrition.

To compensate, fortification was introduced to “replace” what had been lost.

But it doesn’t work that way. We aren’t smarter than Mother Nature, and we can’t simply replicate the Whole Food Matrix with synthetic vitamins and additives.

Over time, fortification became mandatory in many countries. In 1941, the U.S. government officially recommended that flour be enriched with iron, B vitamins, and folic acid.

Today, most modern wheat is “enriched” with:

- Iron (metallic iron filings)

Industrially added iron (in the form of ferrous sulfate) can contribute to iron overload and increase oxidative stress causing widespread cellular damage. (ref) It is added to bread, flour, pasta, cereals, and most packaged food requiring wheat. As a result, Western society has seen an overwhelming increase in iron shaving consumption, largely due to the mandatory fortification of grain products. However, the amount of added iron reported on food labels is often grossly underreported. [ref] Many labels list "reduced iron," which is misleading terminology—it actually means iron is added in the ferrous form, which is very reactive and easily absorbed by the body.

What's particularly concerning is that food fortified with iron does very little to prevent anemia, the condition it was intended to address. Sweden and Finland implemented iron fortification in their food until 1995, and Denmark until 1987, before banning it due to health concerns and low bioavailability. After stopping iron fortification, iron deficiency anemia remained virtually unchanged in those countries [r], suggesting the practice may offer more risks than benefits.

- Folic acid (the synthetic form of Vitamin B9)

Unlike naturally occurring folate in whole grains, folic acid must be converted in the body to its active form, tetrahydrofolate. Not everyone performs this conversion efficiently, leaving unmetabolized folic acid in the bloodstream (ref), which can disrupt natural folate pathways and overall B vitamin metabolism.

- Other synthetic B vitamins like niacin, riboflavin, and thiamin.

Modern flour is processed so aggressively that it strips away the grain’s naturally occurring nutrients. Manufacturers then attempt to “fix” it by adding synthetic vitamins and minerals back in.

Again, it’s unrealistic to think we can replicate nature’s intricate design with isolated additives, which often lack the same bioavailability, balance, and synergy found in whole grains.

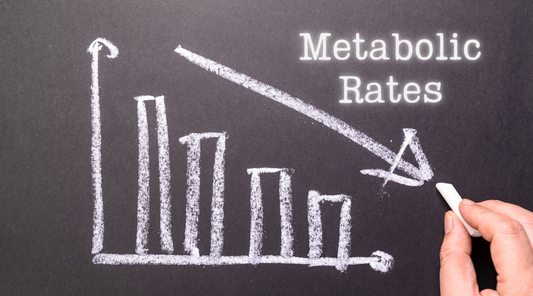

We’re now seeing the consequences of this fortification: iron overload from industrial iron fortification, disruptions in B vitamin metabolism, and negative effects on energy production and overall metabolism. While the fortification program may have begun with good intentions, it has created more problems than it has solved.

In fact, there is substantial evidence in the scientific literature that there is an increase in iron accumulation in tissues with aging. (ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref) We really don’t need more of it fortified into our flour.

Toxic Bleaching and Bromating

Bleaching flour was originally used for appearance and marketability. In the early 20th century, consumers associated whiter flour with higher quality and freshness, so millers used chemicals like chlorine gas, benzoyl peroxide, or chlorine dioxide to make flour look more appealing.

There was also a functional reason: bleaching slightly alters the flour’s protein structure, which can improve baking performance for industrial breads and cakes: making them lighter, softer, and more uniform in texture.

Now, bleached flour is often preferred in certain baking applications, like cakes and pastries, because it produces a finer texture and a lighter color in the finished product. However, a similar fine texture and uniform consistency can be achieved without chemical bleaching through traditional methods like sifting, bolting, or multiple passes through mills. While this approach may be more time-consuming and costly, it preserves some nutrients and avoids chemical residues.

Image from (ref)

Bromation, introduced in the 1930s–1940s, adds potassium bromate to strengthen dough and produce taller, fluffier loaves. While this may improve rise and texture for industrial baking, bromate is now banned in many countries due to its potential carcinogenic effects when residues remain in the flour. (ref)

Essentially, these processes were cosmetic and commercial decisions, not nutritional ones.

Together, bleaching, bromating, and modern industrial milling reflect a purely commercial approach: flour is made visually appealing, uniform, cheap, abundant, and shelf-stable; but at the cost of stripped nutrients, lost bioactive compounds, exposure to potentially harmful chemicals, and a complete disconnection from traditional cultural preparations.

Modern Day: Highly Processed, Genetically Manipulated Wheat

Over the last 50–70 years, two major shifts in agriculture have further altered the flour we eat today. Industrialization and mass chemical use have changed both how we farm and the food it produces.

- Hybridized & selectrively bred wheat varieties

The wheat of today bears little resemblance to the heritage varieties our ancestors consumed. Over the last century, wheat has been systematically bred for higher yields, disease resistance, and industrial processing compatibility, not nutritional value or digestibility.

While modern wheat is not yet genetically modified in the traditional sense (the first GMO wheat variety for drought resistance was only approved in the US in August 2024 [r]), selective breeding programs have altered protein structures and created varieties that produce more grain per acre, but may be harder for humans to digest.

The result?

Higher profits for industrial agriculture but potentially more digestive distress for consumers.

2. Pesticide use (especially glyphosate)

It is well known that millions of wheat fields are treated with pesticides to control weeds, fungi, and insects. Glyphosate is widely used, but that’s just the beginning. Farmers also commonly use fungicides like propiconazole, tebuconazole, and chlorothalonil, as well as insecticides such as imidacloprid and clothianidin to protect wheat from fungal infections and insect damage.

In addition, many wheat seeds are treated with pesticides (like fungicides and insecticides) before they are even planted to “protect” young seedlings from disease and insects, but the chemicals can be absorbed into the growing plant and persist in the grain. This means that even if no additional pesticides are sprayed later in the season, residues from seed treatments can still be present in the harvested wheat.

Image from (ref)

But perhaps one of the most concerning modern agricultural practices affecting the digestibility of wheat is pre-harvest desiccation: a process largely unknown to consumers but increasingly linked to digestive health problems.

Even though wheat is not typically a GMO crop, glyphosate use on wheat has skyrocketed by 400% in the past two decades. [r] Why? Because farmers discovered they could use this herbicide as a drying agent, particularly in regions with short growing seasons or wet harvests.

"The herbicide, glyphosate, is applied to wheat crops before harvest to encourage ripening resulting in higher glyphosate residues in commercial wheat products within North America." [r]

This ‘pre-harvest desiccation’ practice involves spraying crops with glyphosate shortly before harvest to force uniform drying and enable earlier harvesting. Originally developed in 1980s Scotland to address unreliable grain drying conditions, the technique has spread globally.[r]

The result? Non-GMO wheat can receive a "glyphosate bath" before harvest, meaning residues end up in your daily bread (and other baked goods made with wheat).

Research has begun linking glyphosate exposure to the rise in celiac disease and other digestive disorders. [r] The mechanism makes logical sense: glyphosate is designed to kill weeds and microorganisms in soil, but our digestive systems contain trillions of beneficial microorganisms essential for health.

"Glyphosate residues on food could cause dysbiosis, given that opportunistic pathogens are more resistant to glyphosate compared to commensal bacteria." [r]

In other words, glyphosate exposure through food may preferentially kill beneficial gut bacteria while allowing harmful bacteria to flourish: a recipe for digestive distress and chronic inflammation.

What about regulation?

Big Ag companies control our food system and government “regulatory” agencies. The U.S. does not require pre-market pesticide testing on each shipment or batch of wheat before it is sold domestically. And testing is surveillance-based or ‘as needed’, and enforcement via the FDA is rare.

The U.S. has some of the most lenient pesticide residue limits in the developed world, especially for glyphosate, fungicides, and post-harvest insecticides. The European Union (EU), for example, enforces stricter maximum residue limits (MRLs), often 10–100 times lower than U.S. standards, and conducts more frequent systematic testing. Plus, many pesticides allowed on U.S. wheat including glyphosate, chlorpyrifos, and paraquat are restricted or banned. EU MRLs are often 10–100x lower than those allowed by the EPA. The EU also conducts more frequent and more systematic testing.

The consequences of these two changes?

This combination of altered wheat and heavy pesticide coating has led to:

- Altered gluten structures

- Digestive discomfort

- Lower nutrient density

- Chemical residues in the final product

Today’s bread and flour is fundamentally different from what your ancestors ate.

Industrial farming has prioritized quantity, uniformity, and shelf-stability over nutrition, digestibility, and traditional preparation methods.

The Lost Art of Fermentation

In addition to the dramatic changes in wheat berries and flour, bread-making itself has shifted: largely for speed, cost, and efficiency.

For thousands of years, people relied on sourdough fermentation to make bread digestible. This natural process, driven by wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria, slowly leavened the dough, breaking down gluten and phytic acid while introducing beneficial microbes like Lactobacillus reuteri, the same bacteria that can be passed from mother to baby during breastfeeding to produce a healthy microbiome balance.

The evolution of bread fermentation tells the story:

- Ancient times through the 1800s: Most bread was made using wild fermentation methods like sourdough or yeast sourced from breweries. Slow fermentation developed complex flavors and improved digestibility by breaking down difficult proteins.

- Mid-1800s: As brewing became more industrialized, bakers began using yeast extracted from breweries (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). This yeast produced a faster rise than traditional sourdough, but reduced the natural fermentation timeline slightly.

- Early 1900s: The demand for faster, more predictable baking led to commercial yeast cultivation, allowing bakers to produce loaves in hours instead of days.

- Mid-1900s to present: Instant yeast and active dry yeast dominate commercial baking, offering speed and consistency but eliminating the microbial diversity and slow fermentation that made traditional bread both flavorful and more digestible.

Today, commercial yeast allows mass production of bread that is reliable, uniform, and fast: but it lacks the depth, texture, and potential digestive and nutritional benefits of traditional sourdough. The trade-off is convenience over the natural processes that supported health for thousands of years.

Returning to the Roots: Heritage & Ancient Grains

Heritage and ancient varieties (like Rouge de Bordeaux, Turkey Red, einkorn, spelt, rye, and millet) have not been genetically altered, preserving their original structure, nutrient profile, and flavor.

When grown regeneratively and stone-milled fresh, they offer:

- - better digestion

- - deeper flavor

- - improved nutrient density

- - no pesticide exposure

In fact, a growing body of anecdotal evidence suggests that many people find heritage and ancient grains easier to digest than modern wheat.

Some studies also indicate that these older wheat varieties may provoke a lower inflammatory response, possibly due to higher levels of polyphenols and other bioactive compounds. (ref) Additionally, research on the gut microbiome indicates that ancient wheats may help favorably modulate gut flora, supporting digestive health and improving carbohydrate metabolism. (ref)

Likely because they are different foods!

Modern Wheat vs. Heritage Grains

1. Genetic Differences: Modern wheat has been selectively bred over the past century for higher yields, pest resistance, and uniformity, prioritizing industrial processing over digestibility or nutrient quality.

2. Fortification: Modern flour is often harshly milled then artificially enriched with synthetic vitamins and minerals, which can disrupt natural nutrient pathways.

3. Pesticide Load: Modern wheat is frequently grown with chemical pesticides, and many seeds are treated before planting, leaving residues in the final flour.

4. Bleached and bromated: Industrial processes alter the flour for aesthetics and shelf stability, but at the cost of nutrients and bioactive compounds, and exposure to more chemicals.

5. Protein and Gluten Structure: Modern wheat contains higher concentrations of certain gluten proteins, optimized for elasticity and shelf life, which can be harder for some people to digest. Heritage grains generally have a more balanced gluten composition and intact protein structures, gentler on the digestive system.

6. Nutrient Density: Industrial milling strips modern wheat of its natural vitamins and minerals, which are then partially replaced with synthetic nutrients. Heritage grains retain their full spectrum of B vitamins, minerals, and beneficial polyphenols.

People often tolerate heritage grains better because:

- They contain less concentrated and more naturally structured gluten.

- They are higher in fiber and beneficial compounds that support digestion.

- Traditional preparation methods (soaking, sprouting, sourdough fermentation) break down anti-nutrients like phytic acid, improving nutrient absorption and making the grain easier on the gut.

Bottom line: Heritage grains offer a more nutrient-rich, flavorful, and digestible alternative to modern wheat, closer to how our ancestors consumed bread for thousands of years.

This is exactly the kind of flour Nourish Food Club brings to your kitchen: flour your ancestors would recognize, and flour your body can truly thrive on.

The Nourish Flour Difference

Our chemical-free heritage and ancient grains are grown using regenerative agriculture practices where our farm partners work with nature, not against it. That means no pesticides, no heavy tillage, and farming methods that restore the soil rather than deplete it.

Instead, our farmers rely on time-honored, soil-building practices, including:

- > Diverse crop rotations that break pest cycles naturally

- > Cover crops to protect and nourish the soil

- > Working with the seasons rather than forcing artificial growth

- > Keeping living roots in the ground as much as possible to support microbial life

Once harvested, grains must be milled to transform them into flour. While modern roller mills dominate industrial flour production, we choose the time-honored method of stone milling to preserve the integrity of the grain.

Stone milling is a slower, gentler process where whole grains are crushed between two large natural or engineered stones. Unlike high-speed roller mills, which strip away the bran and germ to produce ultra-refined flour, stone milling retains the grain’s natural vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols, delivering flour that is both more nutritious and richer in flavor.

Because stone mills generate less heat, delicate nutrients remain intact, and the resulting flour has a coarser texture with more depth and character. Many bakers and home cooks report that stone-milled flour produces superior-tasting sourdough bread and other baked goods, with a heartier, more satisfying bite.

At Nourish, we are committed to milling methods that honor both tradition and nutrition, ensuring our flour delivers the highest quality in taste and nourishment.

> Heritage and ancient grains

> Regeneratively Grown

> Lab-tested pesticide free for over 750 pesticides

> Stone-Milled

The Nourish Line Up of Heritage and Ancient Grains:

By choosing Nourish Flour, you’re voting with your dollar against the chemical-intensive, industrial agriculture system that depletes topsoil and pollutes our environment.

Instead, you’re supporting regenerative agriculture: practices that restore soil health, boost nutrient density and flavor in food, and reduce pesticide exposure for our planet and our communities.

> Shop Heritage and Ancient Flour