The Hidden Cause of the Obesity Epidemic: Calories Out Are Crashing

America is in the midst of a full-blown obesity crisis, now recognized as a global health emergency. 1 Today, 30.7% of U.S. adults are classified as overweight, while a staggering 42.4% meet the criteria for obesity. 2

This means that nearly 7 in 10 adults are categorized as either overweight or obese—an alarming statistic that signals deep dysfunction in our modern lifestyle and food system.

For decades, we’ve been told that obesity is simply the result of overeating and not moving enough. But what if we’ve been missing a major piece of the puzzle?

Yes, gaining weight happens when there’s an energy surplus—when you’re taking in more calories than your body burns (calories in > calories out).

But here’s the twist: our ancestors ate more calories than we do today—yet they remained lean, strong, and active.

By contrast, we’re gaining weight while eating the same—or even fewer—calories. So what gives?

This raises a critical question: Is the problem really just too many “calories in”? Or is something causing our “calories out” to decline?

Both sides of the energy equation matter.

Sure, overeating can lead to weight gain. But here’s the thing—many people today are gaining weight even when they’re not overeating. Why? Because their bodies aren’t burning through energy like they used to.

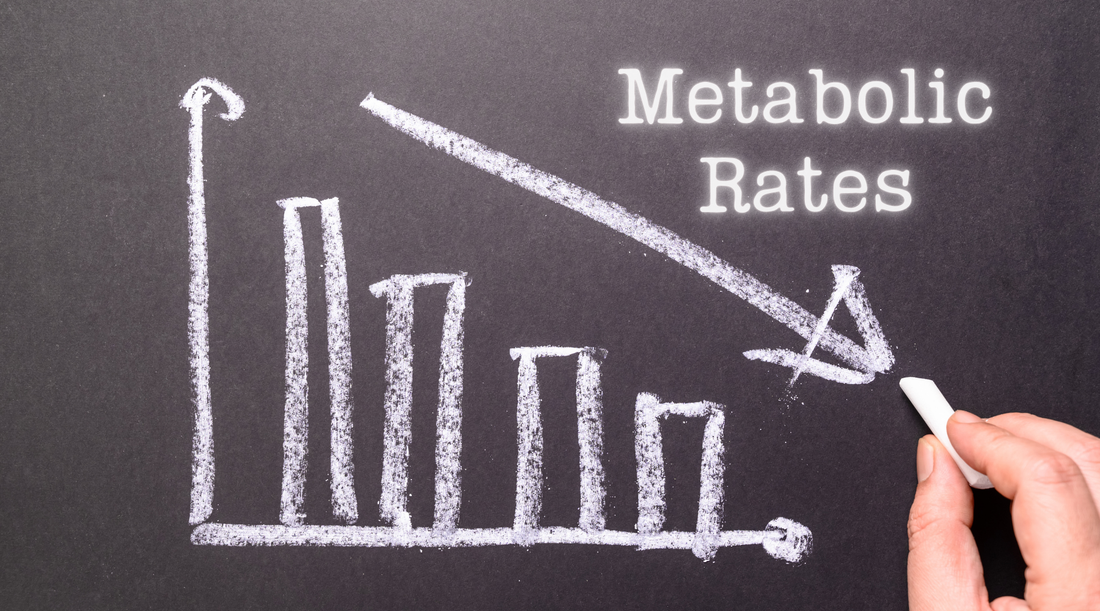

The “calories out” side of the equation has been downregulated. Our metabolic engines are running colder.

Obesity is a complex, multifactorial issue that deserves a nuanced conversation. But one thing is clear: our basal metabolic rates—the amount of energy we burn at rest—are declining.

And this is being driven, in large part, by lifestyle factors and profound changes in our food system.

Metabolic dysfunction is becoming the norm, not the exception: 93% of Americans are not metabolically healthy, and over one-third of adults have prediabetes. 3

Our metabolism is not working the way it should. And that’s a big deal.

So in this post, let’s dive into why our metabolisms have been downregulated, what the consequences are, how the food system has changed, and wrap up with simple, actionable tips to support and revive your metabolic rate naturally.

But first, what even is ‘metabolism’?

At its core, metabolism is how your body turns food into energy.

When you eat, your body breaks food down into smaller pieces—mainly glucose (from carbs), fatty acids (from fats), and amino acids (from protein). These molecules carry high-energy electrons in their chemical bonds.

Your body’s goal? Turn that energy into ATP (adenosine triphosphate)—the main fuel your cells use to do their jobs.

Metabolism is essentially energy conversion to convert the food you eat into a form of energy your cells can use.

This transformation happens in your mitochondria, the “power plants” of your cells. As electrons are passed along a special pathway (called the electron transport chain), they release energy that your mitochondria use to produce ATP.

Think of it like a controlled fire: food gives us the fuel, and mitochondria spark that fuel to create energy we can actually use.

When your metabolism is running efficiently, this process hums along—producing plenty of energy to support everything from digestion to brain function.

But when your metabolism is downregulated, this energy-making process slows. That’s when problems begin.

Why should I care?

When your metabolic rate slows down, two major things happen:

1. You Store More Fat

One of the top reasons to care about your metabolism is because it plays a huge role in how easily you can maintain a healthy weight—and that’s something many people struggle with today.

When your metabolism slows down, your body burns fewer calories both at rest and during daily activities. That means your total “calories out” drops. So even if your eating habits haven’t changed, it’s now easier to end up in a calorie surplus—and gain fat.

To keep weight stable, you’d have to eat less than you used to, simply because your internal engine isn’t burning as much fuel.

On the flip side, a well-functioning metabolism means your body is more efficient at turning food into usable energy. Instead of storing that energy as fat, you burn through it to power your cells and fuel your life.

There are of course limitations to this – you can’t eat an endless amount of food and expect your body to burn it all. But it’s a big deal when your body turns the dial down in energy production and reduces your ‘calories out’.

A faster, healthier metabolism helps your body use fuel—not store it.

2. You Make Less Energy

A slower metabolism means less ATP produced. And since every cell in your body needs ATP to function, that’s a big deal.

Low energy production can lead to fatigue, brain fog, poor digestion, hormonal issues, weakened immunity, lower rates of detoxification and more…

Energy is your body’s most precious resource. The more resources you have, the better you function and the more you can do.

When it’s in short supply, your body starts cutting corners—shutting down or down regulating non-essential functions and relying on backup systems that aren’t as efficient. The body prioritizes the vital functions that keep you alive: like maintaining your breath and vision.

Many chronic health conditions can actually be traced back to poor energy production at the cellular level since lower energy levels inhibit proper function and structure of tissues.

As Dr. Geary explains:

“Mitochondria produce cellular energy in the human body, and energy availability is the lowest common denominator needed for the functioning of all biological systems. With good mitochondrial function, the aging processes will occur much more slowly.”4

Generations before us had higher metabolic rates and were able to maintain a healthy weight with ease. So... what changed?

Energy Balance

Before diving into the research, let’s quickly review the concept of energy balance—the relationship between the energy we consume through food and drinks (calories in) and the energy we expend through various bodily functions and activity (calories out).

Your total “calories out” is made up of four main components, as shown in the image below:

Together, EAT and NEAT make up Activity Energy Expenditure (AEE)—the total calories your body burns through both intentional exercise and everyday movement.

While many people assume that physical activity is the biggest lever for burning calories, the truth is a bit surprising. As you can see from the image, the largest contributor to your total daily energy expenditure is actually your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—which accounts for nearly 70% of your “calories out.” In other words, your metabolism—how efficiently your body processes and uses energy—plays a dominant role in energy balance.

Yes, movement and exercise are important for overall health. But when it comes to calorie burning, your BMR carries the most weight.

So yes—weight gain ultimately comes down to consuming more calories than you burn. But here’s the key: the “calories out” side of the equation isn’t fixed. It’s dynamic. It can be influenced—and even increased—through your diet, lifestyle, and overall metabolic health.

But what if something has caused a significant drop in our basal metabolic rate (BMR)—the biggest part of our daily energy burn?

What if our metabolic engines are running slower than they used to?

Well… they are.

And the science backs it up.

The Research Documenting a Decline in BMR

Let’s look at one of the most groundbreaking studies on this topic: a 2023 review paper led by Dr. John Speakman, a globally recognized researcher in the field of metabolism.

For decades, it’s been assumed that the rise in obesity is mostly due to modern life making us more sedentary—less physically active—combined with overeating. But Dr. Speakman’s team challenged this long-held belief. And what they found shocked the field.

They documented that our total “Calories Out” has definitely declined over the last few decades—but not because of reduced activity.

In fact, when they broke down the components of energy expenditure we discussed above, they found that Activity Energy Expenditure (AEE)—the calories burned through exercise and daily movement—has increased over the past 30 years. So no, we’re not necessarily moving less.

The real drop came from our Basal Metabolic Rates (BMR)—the energy your body burns at rest to carry out essential functions like breathing, pumping blood, and maintaining body temperature.

“What that means is that your resting metabolic rate now, as a person living in 2023, is lower than a person of your age and body composition from the late 1990s.” — Dr. John Speakman

In other words, we now burn significantly fewer calories at rest—by about 200 to 300 calories less per day. That’s equivalent to the energy in a small meal… burned off just by existing. This helps explain why even active people may struggle to maintain or lose weight if their metabolic rate is suppressed.

Dr. Speakman concluded:

“The magnitude of this effect is sufficient to explain the obesity epidemic.”

So while overeating can definitely contribute to weight gain, a declining BMR across the population is a massive red flag that deserves more attention.

What’s even more fascinating is that these findings align with another long-term trend: a steady decline in average body temperature over the past century.

Why does this matter?

Body temperature is a marker of metabolic rate. When your metabolism is firing and your body is efficiently producing energy, heat is generated as a byproduct. That heat keeps your body temperature elevated. So:

- Higher body temp = higher metabolic rate (more energy production)

- Lower body temp = lower metabolic rate (less energy production)

Image from 5 . “Decreasing human body temperature in the United States since the Industrial Revolution”

As Dr. Speakman noted: “This reduction in BMR is consistent with the recent observation that body temperatures have also declined over time, over the same interval as the reduction of BMR in the wider data set we analyzed”

Now, combine this decline in metabolic rate with modern food abundance—ultra-palatable, calorie-dense foods everywhere—and it becomes clear:

Gaining weight is easier than ever before.

If your body is burning fewer calories at rest, even a “normal” intake of food can push you into a calorie surplus. That’s why so many people are doing their best—eating reasonably, moving regularly—but still having trouble maintaining a healthier weight.

A Blast from the Past: How Much Did Our Ancestors Eat?

So, the science proves the downregulation of our BMR.

But before we get into why our basal metabolic rate has declined, let’s take a step back in time.

In the past, eating more food wasn’t shamed—it was celebrated. Our great-grandparents could consume significantly more calories than we do today, yet remain lean and metabolically healthy.

A striking example comes from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment (MSE), conducted in the 1940s. The participants were lean men aged 20–33, with an average weight of 152 lbs and a height of 5’10”. Despite their slim builds, their maintenance calorie requirement—the amount they could eat without gaining weight—was a staggering 3,500 calories per day.

For context, the average calorie intake in America today is around 3,500–3,600 calories per day. Yet, unlike the MSE participants, obesity rates are now at an all-time high.

The MSE was incredibly meticulous. Every bite of food was prepared and weighed by professional chefs, and participants’ activity was tightly controlled. They weren’t doing intense workouts, just consistent movement: 10,000-12,000 steps per day, one weekly “cardio session” (which was a 30 minute walk at 4.5 mph on a treadmill), and weekly engagements in 25 hours of university classes and 15 hours of maintenance work (e.g., laundry, clerical tasks)

Their daily meals equating to ~3500 calories included starches, fruits, desserts, dairy, and meat—yes, even ice cream. Notably, the fats were primarily saturated fats, with very low levels of polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs).

Curious about what a modern calculator says? I checked an online calorie calculator for a 5’10”, 152 lb, 30-year-old male walking 10k–15k steps per day (the equivalent of the subjects in the MSE)):

“To maintain weight, he should eat 2,065–2,415 calories per day.”

That’s a full 1,000 calories less than what the lean participants were eating in the 1940s to maintain their weight!

And this isn’t just a one-off example. Let’s dive into some more historical cues to better understand how much food our ancestors ate.

For example, check out this image from ‘Eating for Strength’ published in 1888. The ‘Subsistence diet’ was 1714 calories – which is the minimum calorie needs for survival. Meaning, the bare minimum – just enough to survive, not thrive. Many people are eating this amount of calories today on restrictive diets! You can also see on that list that the recommended calorie intake for someone performing ‘moderate exercise’ was 2936 calories!

A subsistence diet typically prioritizes meeting the minimum caloric needs for survival. While it can sustain life, it is unlikely to support the full potential of human health, energy, and vitality. Thriving and optimal health require more calories to meet all physiological and lifestyle demands.

Here is a screenshot from ‘The Science of Nutrition’, published in 1888, where the author discusses how a base level of calories is required for ‘the internal work of the body’ (meaning, calories required to keep you alive, excluding calories required for activity). The author recommended closer to 3000 calories when considering activity levels on top of the ‘life ration’ (similar idea to the ‘subsistence diet’).

Here is an image from the 1939 USDA Yearbook of Agriculture which reveals a clear trend: the more money someone had, the more food they consumed – some eating up to 5000 calories per day.

And finally, a screenshot from ‘Cookbook 365’ published in 1915 shows that many modern restrictive diets are matching the caloric intake of 9-year-olds in the early 1900s, eating 1800-1900 calories.

But didn’t they just move more?

That’s the narrative we often hear: “People were thinner back then because they were more active.”

Well… yes and no.

It’s true that some people today are overly sedentary and would benefit from moving more. But the data doesn’t support the idea that a drop in physical activity alone is responsible for the obesity epidemic.

As Dr. Speakman’s research shows, the total energy expenditure (TEE) hasn’t gone down due to movement. Instead, the issue is a decline in BMR—the calories we burn at rest.

“Overall, the data we present do not support the idea that lowered physical activity in general, leading to lowered energy expenditure, has contributed to the obesity epidemic during the last 30 years… We conclude that increasing obesity in the United States/Europe has probably not been fueled by reduced physical activity leading to lowered TEE. We identify here a decline in adjusted BEE [which is related to Basal Metabolic Rate, BMR] as a previously unrecognized factor.”6

Today, the average American walks between 5,117 and 6,540 steps per day. 7, 8 That’s too low, as walking and activity is essential for health. Ideally, we’d aim for 8,000–12,000 steps daily.

Here’s the kicker: Hitting 12,000 steps per day only burns about 131 more calories than walking 5,000 steps per day.

Again, that drop in movement isn’t enough to explain the explosion in obesity.

So, should we be walking 30,000 steps per day to crank up our calorie burn even more?

No! Walking 10,000 steps per day is a great health habit, and staying active is essential. But more isn’t always betterwhen it comes to burning calories.

Your body has finite resources, and how quickly they’re drained depends on the demands placed on it. Push too hard, and you risk overtraining, which can disrupt thyroid function, suppress metabolism, and lead to a cycle of diminishing returns.

“The present investigation demonstrates that the thyroid function is strongly affected by prolonged physical exercise and a negative energy balance.”9

Yes, movement matters. But there’s a tipping point where exercise becomes a stressor, and the body starts pulling energy away from other functions to keep up. You can’t endlessly burn more without consequences—because humans, well… we’re not machines.

So what should we focus on?

Hit reasonable activity goals—10,000 steps a day is a good benchmark.

But even more importantly, we need to support and improve our BMR.

That’s the true engine of your metabolism.

We should be able to eat more food and more effortlessly maintain a healthy bodyweight.

Why has our BMR declined?

If we want to improve our BMR, we first need to understand why it’s been downregulated in the first place.

There are several contributing factors—but the food we eat every single day plays the biggest role. And unfortunately, our modern food system has radically shifted over the past century.

Simply put: the food system is no longer working for us.

Today, we’re exposed to what I call “the 3 Ps” like never before: PUFAs, Phytoestrogens, and Pesticides.

Together, these 3 Ps are working against your metabolism, not with it.

They interfere with your ability to convert food into energy, leading to:

- Less ATP (cellular energy) being produced

- More calories being stored as fat

- A lower basal metabolic rate

Worst of all? These effects are compounding.

It’s not just one problem—it’s a stack of stressors, pushing the body into conservation mode and slamming on the metabolic brakes.

The First P: The PUFA Overload

One of the most dramatic dietary shifts over the last 100 years is in the types of fats we consume.

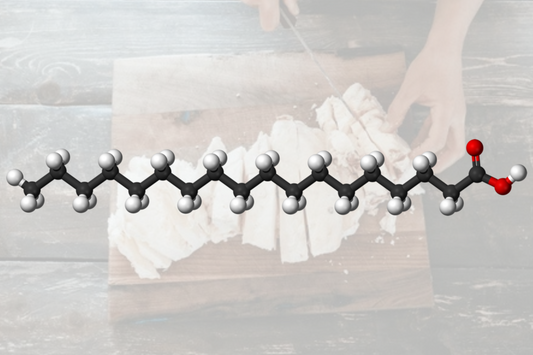

We’ve swapped out butter, tallow, and ghee for margarine, soybean oil, and industrial seed oils—all rich in plant-based polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) like Linoleic Acid (LA, an Omega 6) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, an Omega 3).

But the problem doesn’t stop with what we cook with.

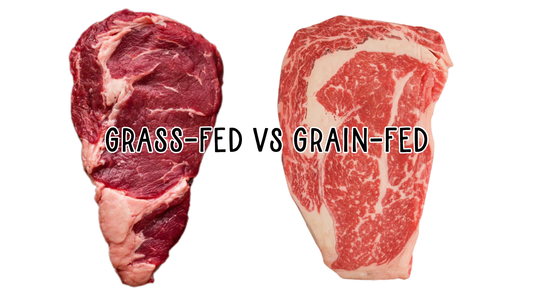

Today, livestock are packed into confined buildings and fed PUFA-rich rations—soy, vegetable oil, flax and byproducts liked Dried Distiller Grain Solubles (DDGS) that were never part of their natural diet.

As a result, the fatty acid composition of animal products has changed, too. The meat, milk, and fat we consume from these animals now contains more unsaturated fats and less saturated fat compared to what our ancestors ate—even if it looks the same on the plate.

In short, today’s diet is heavy in plant-based PUFAs and low in traditional saturated fats from nutrient-dense animal sources.

This shift in dietary fat matters. And it’s impacting our metabolism at the cellular level.

Even Dr. John Speakman, in his landmark 2023 review documenting the decline in basal metabolic rate (BMR), noted:

“Basal metabolism may be influenced by many factors one of which is diet. Human dietary changes during the epidemic have included many things such as changes in the amounts of fiber and fat, and the types of fat consumed… The change has been dramatic, as animal fats comprised >90% of the fatty acid intake in 1910 but are currently less than 15%.... This suggests that alterations in the intake of saturated relative to unsaturated fat over the last 100 years may have contributed to the decline in BEE reported here” 10

Since 1909, plant-based PUFA exposure has increased by 238%.11

Why does this matter?

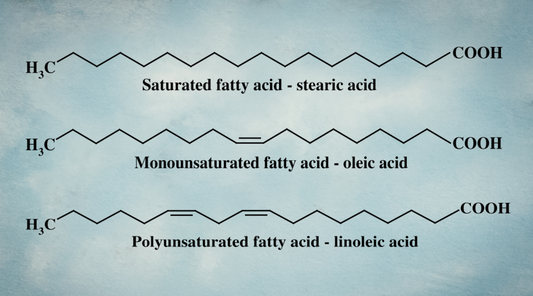

All fats contain a mix of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids—but the ratios vary drastically depending on the source. For example:

- Butter and cheese are high in saturated fats.

- Margarine and seed oils are rich in PUFAs.

Even if they have similar total fat content, their structure determines their function. And that structure affects cellular health, enzyme activity, and energy production in a big way.

So at the cellular level, saturated and unsaturated fats are processed very differently.

Saturated fats (like stearic acid) go through complete beta-oxidation, a process that efficiently produces energy-carrying molecules like FADH2, which feed into the mitochondria’s electron transport chain to produce ATP—your body’s energy currency.

In contrast, PUFAs burn less efficiently, produce less ATP, generate more oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and lead to electron leakage and damage mitochondrial function. 12, 13

PUFAs lower your metabolic rate 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 , causing your body to burn fewer calories at rest, which means you can gain weight more easily, even without increasing your food intake.

Due to the downregulation of metabolism, excessive intake of linoleic acid and other plant-based PUFAs has been shown to promote fat gain and may be a major contributing factor to the obesity and diabetes epidemics. 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

One study noted: “Our results indicate that, contrary to expectation, PUFA-rich soybean oil is more obesogenic and diabetogenic than coconut oil which consists of primarily saturated fat….While this study was in progress, two groups published papers with results similar to ours—namely, that a high fat diet supplemented with oils high in LA leads to obesity and fatty liver…Other studies have also shown that dietary LA can cause adiposity in humans…and lead to hyperglycemia as well as obesity in mice.”31

PUFAs also inhibit enzymes necessary for proper carbohydrate metabolism 32, 33 , disrupting glucose utilization and promoting fat storage. This leads to a loss of metabolic flexibility—your body’s ability to seamlessly switch between burning carbs and fat for fuel.

Saturated fats, on the other hand, support enzyme activity and maintain metabolic flexibility, helping your body burn glucose efficiently and generate steady energy.

Here is a quote from Dr. Speakman himself – “While it’s difficult to precisely control human diets in studies, mouse models allow for rigorous, long-term dietary control…. mouse data indicate that one of many possible explanations (for the obesity epidemic) is decreases in the intake of saturated relative to unsaturated fatty acids… In these mouse models, higher intake of saturated fat has been shown to increase metabolic rate (adjusted for body mass). This supports earlier findings that link membrane lipid composition to elevated metabolic rate in mice—particularly the beneficial effects of palmitic and stearic acids (saturated fats).” 34

TLDR: We changed our fats, and we broke our metabolism.

The type of fat you eat influences the type of fat you store, how much energy you burn at rest, and whether your body operates in a mode of burning or storing.

Generations before us thrived on diets higher in traditional saturated fats like stearic acid and C15:0. These fats supported strong metabolic health and stable energy.

The rise of PUFAs and the decline of traditional saturated fats in our food system is one of the most overlooked but powerful contributors to our declining BMR and to the modern metabolic health crisis.

The Second P: The Phytoestrogen Problem

As PUFAs crept into our food system, so did another class of metabolic disruptors: phytoestrogens - powerful plant compounds that mimic estrogen in the body. 35

Two of the biggest offenders are soy and flax. And it’s not just from the food we eat directly—it’s also hidden in the feed given to livestock raised in industrial systems. These estrogenic compounds accumulate up the food chain, ending up in the meat, milk, and eggs we consume. 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Over time, chronic exposure can disrupt hormone balance, impair thyroid function, and lower metabolic rate 41 , further hitting the brakes on energy production.

Phytoestrogens have also been shown to interfere with the transport of thyroid hormones in the blood Several studies support the impact of diet on metabolic health 42, 43, 44.

It’s worth understanding where these ingredients came from.

Soy is a relatively new addition to the food system. Flax, historically used to make linen and industrial paints, was never part of the ancestral diet. The high PUFA content of soy and flax oxidizes quickly—perfect for hardening paint, but damaging inside the human body. Yet today, these compounds are everywhere in our food system—boosting both PUFA and phytoestrogen exposure to levels never seen before.

“50 years ago, paints and varnishes were made of soy oil, safflower oil, and linseed (flax seed) oil. Then chemists learned how to make paint from petroleum, which was much cheaper. As a result, the huge seed oil industry found its crop increasingly hard to sell…

Around the same time, farmers were experimenting with poisons to make their pigs get fatter with less food, and they discovered that corn and soy beans served the purpose, in a legal way. The crops that had been grown for the paint industry came to be used for animal food. Then these foods that made animals get fat cheaply came to be promoted as foods for humans.”

—Dr. Ray Peat

Today, we’re exposed to estrogenic compounds like never before.

Estrogen and progesterone are meant to exist in a delicate balance—like yin and yang. But modern diets and lifestyles have tipped the scale toward estrogen dominance, a hormonal imbalance that’s becoming alarmingly common.

Estrogen dominance disrupts insulin sensitivity, increases fat storage, and slows energy expenditure. Low progesterone reduces thyroid support and impairs glucose metabolism. 45

And the result? A sluggish metabolism that’s primed for fat gain.

Estrogen dominance doesn’t just mess with hormones—it slows down your entire metabolic engine. One key mechanism? Estrogen raises levels of thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) 46, 47 - a protein that binds to T3, your active thyroid hormone. When more T3 is bound, less is available to your cells—and that means less energy production. T3 is like a spark plug for your metabolism. Without it, your metabolic fire dims.

Estrogen dominance → less available T3 → slower metabolism → easier weight gain

No wonder estrogen is used in the livestock industry as a fattening agent. 48

When you pair PUFAs and phytoestrogens, you create the perfect storm: a fat-promoting, energy-suppressing environment that leads to weight gain, fatigue, and metabolic dysfunction.

The Third P: PESTICIDES

The modern industrial food system is built on a foundation of synthetic pesticides.

Pesticides are chemical substances used to kill or repel pests like insects, weeds, and fungi that threaten crop yields. Some examples include Glyphosate (the active herbicide ingredient in RoundUp), Atrazine, and 2,4-D.

But while they may “protect” crops and boost production, they can wreak havoc on human biology.

When you try to fight nature with chemistry, there are always consequences.

Just like PUFAs, many pesticide compounds interfere with your body’s ability to make energy. 49, 50, 51 And like phytoestrogens, they act as endocrine disruptors 52, 53, 54 —fueling hormonal imbalances and pushing more people into estrogen dominance.

This double-hit slows your metabolic engine and shifts your body toward fat storage.

Certain pesticides, like glyphosate, boscalid, and rotenone, directly damage mitochondria—the energy factories inside your cells. They block critical steps in the electron transport chain (ETC) 55 , reducing your ATP output (your cellular energy currency). 56

- Rotenone inhibits Complex I 57

- Glyphosate blocks Complex II and III 58, 59 — and acts as a chelating agent, stealing key minerals like iron, copper, zinc, manganese, calcium, and magnesium. These are all critical for mitochondrial energy production.

It’s no wonder glyphosate has been shown to reduce mitochondrial function by nearly 50% in rat liver cells 60 and lower ATP production in human sperm cells, reducing both sperm motility and sperm function, hindering fertility. 61

It gets worse.

Glyphosate increases mitochondrial membrane permeability, triggering leakage, oxidative stress, and cellular dysfunction. 62, 63

By interfering with a number of steps along the ETC 64 , Glyphosate and RoundUp exposure and lower your ‘Calories Out.’

The result?

Less energy. More fat storage. Greater metabolic dysfunction.

Image from 65 .

To top it off, these chemicals stimulate the enzymes that create fat (lipogenesis) while suppressing the ones that burn fat (fat oxidation). 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71

And when it comes to exposure, it’s not just what you eat – it’s what your food eats, too.

It’s common knowledge that pesticides are heavily used in conventional crop production—to deter pests during the growing season and, in some cases, as pre-harvest desiccants on grains like wheat, oats, barley, and legumes.

What’s far less discussed is the massive amount of pesticides used to grow livestock feed for both GMO and non-GMO systems.

Each year in the U.S., roughly 1 billion pounds of pesticides are applied to crops meant for human consumption. But another 250 to 300 million pounds are used solely on feed crops like corn, soybeans, and alfalfa. 72

And it doesn’t stop at feed.

Pesticides are also widely used inside confinement animal feeding operations (CAFOs) to control the swarms of insects and rodents drawn to these unnatural, high-density environments. Facilities like indoor chicken houses, hog barns, and cattle feedlots create perfect breeding grounds for pests and disease. Industrial agriculture relies heavily on chemical intervention to keep things manageable.

And these chemicals don’t just disappear.

Many pesticides are fat-soluble. That means when animals consume contaminated feed or are exposed environmentally, the chemicals accumulate in their fat, organs, and milk. 73 Eventually, they make their way into your body, too. 74, 75

Why Is the Food System the Way It Is?

There are consequences to trying to maximize production while minimizing costs.

Over time, the food system has become highly centralized, controlled by just a handful of powerful corporations. And when Big Ag is tightly intertwined with Big Pharma, it’s no surprise that the system prioritizes profits over health.

After all, it’s far more profitable to manage chronic illness than to prevent it!

A food system that slows your metabolism sets the stage for chronic disease—and that’s a goldmine for the pharmaceutical industry. The 3 Ps (PUFAs, Phytoestrogens, and Pesticides) all contribute to a hormonal and metabolic environment that promotes estrogen dominance and lowers energy production.

It’s no coincidence that we’re seeing skyrocketing obesity rates, not just from excess food, but from a downregulated metabolic rate that makes fat easier to gain and harder to lose.

But don’t panic, be proactive.

Understanding these issues is empowering. It helps explain why the quality of your dietary fat sources matters so much.

In today’s world, perfection might not be possible, but progress is. Every step toward higher-quality food makes a difference.

If we want to support our metabolic and hormonal health, we need to return to the practices that nourished generations before us - before industrial agriculture flooded the food supply with compounds that disrupt energy, hormones, and long-term vitality.

Tips to Improve Metabolic Health and Increase Your BMR

We should be able to eat more food without gaining weight, just like our ancestors did for generations. But modern life has introduced several “metabolic brakes” that make this much harder.

The good news? You’re not doomed.

Your metabolism isn’t permanently broken, it has simply adapted to the environment and inputs you’ve given it.

And just like it adapted downward, it can adapt upward.

Your “Calories Out” is not fixed - it can be improved! By supporting energy production and raising your basal metabolic rate (BMR), you can train your body to burn more calories at rest and increase your maintenance intake.

Here are 8 practical tips to retrain your metabolism and build a lifestyle where you can eat more without gaining weight:

1. Prioritize Whole Foods

Cook most of your meals at home using single-ingredient, whole foods. These foods are naturally nutrient-dense and free from additives like gums, preservatives, and seed oils that can interfere with metabolism.

2. Stay Active Daily

Aim for 8,000–12,000 steps per day and include 2–3 planned workouts weekly. You don’t need extreme workouts—movement throughout the day + moderate training is a winning combo. Avoid overtraining, as recovery is essential for metabolic repair.

3. Build Muscle

Muscle is metabolically active - it burns more calories even at rest. Increasing your lean muscle mass is one of the most powerful long-term strategies to raise BMR. This doesn’t happen overnight, but consistent effort pays off over time!

4. Maintain Consistent Eating Habits

Avoid extremes - don’t restrict heavily during the week and then binge on weekends. This creates low energy availability (LEA), which can slow metabolism. Balanced, steady meals throughout the day support consistent energy and hormone balance.

5. Moderate Dietary Fat

Keep fat intake moderate and pay attention to the types of fats you’re eating. Limit unsaturated fats, which impair mitochondrial function and can lower metabolic rate over time. For the fats you do consume, prioritize fats higher in saturated fats such as traditional animal fats, coconut oil, and quality chocolate.

6. Choose High-Quality Foods

Reducing your exposure to pesticides, PUFAs, and phytoestrogens is critical for metabolic health.

- Prioritize corn-, soy-, and flax-free animal products (especially for chicken, pork, and dairy). When these aren’t available, 100% grass-fed ruminant meat (like beef or lamb) is your best bet.

- Use the Environmental Working Group’s Clean 15 and Dirty Dozen lists to help guide organic produce purchases.

- Grains (wheat, oats, corn) should be sourced organically or from trusted farmers due to the common use of glyphosate as a pre-harvest desiccant.

- When you can, knowing where your food comes from and what was used to produce the food will help you limit your exposure to compounds in the food system that are causing metabolic damage.

7. Prioritize Sufficient Carbs

Carbs are not the enemy - your thyroid and metabolism rely on them. Make sure you’re eating enough for your needs, and choose carbs that digest well for you. This supports hormone production and overall energy output.

8. Monitor and Gradually Increase Caloric Intake

Don’t go from 1,500 to 2,500 overnight - that’s a recipe for fat gain when metabolism is low.

Use a tool like Cronometer to track your intake and weight trends. Aim to increase slowly, staying within your maintenance calorie range. The goal is to train your body to maintain or lose fat at a higher calorie intake, not less.

By applying these principles, you can retrain your metabolism, boost your energy, and build a lifestyle where eating more supports, not sabotages, your health.

It’s not about chasing perfection. It’s about making better choices, more often, in a system designed to work against you.

The Nourish Low Ps™ Standard

At Nourish, we created the Low Ps™ Standard to bring real food back to its roots. By eliminating polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), phytoestrogens, and pesticides—the metabolic disruptors that now saturate our food system—we’re restoring the integrity of the food supply from the ground up. This means working directly with regenerative farmers, choosing species-appropriate feed, and staying involved in every step of production—from seed to fork. It’s how food used to be grown: without shortcuts, synthetic chemicals, or hidden toxins. We’re not just building a food company—we’re rebuilding trust in food itself.