The Hidden Hormone Disruptors in Eggs, Meat, and Dairy

We’ve been taught to fear BPA in bottles, pesticides on produce, and phthalates in cosmetics, all well-known endocrine disruptors. But there’s another source of estrogenic exposure most people overlook: their food.

And depending on what that chicken was fed, even your daily egg yolk could quietly be disrupting your hormones.

Let’s unpack it.

From Paint to Plate

Soy and flax weren’t always considered food.

Historically, flax was used for linen and industrial paint.

Soy wasn’t a staple in traditional diets either.

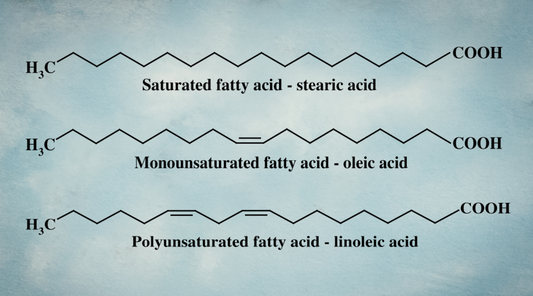

The high PUFA (polyunsaturated fat) content in flax and soy made them perfect for fast-drying applications like paint, not for human consumption.

Today, they dominate our food system, both directly and indirectly through livestock feed (because now they are eating them, too).

The result?

Increased exposure to both unstable fats and hormonally active phytoestrogens, compounds our great-great-grandparents were never exposed to at these levels.

Hormonal disorders are on the rise. Infertility is climbing. Breast cancer has increased by 210% since 1970. Testosterone levels are plummeting.

What's going on?

We’re surrounded by endocrine-disrupting compounds: from cosmetics to cleaning supplies, clothing, and now food.

Soy and flax contain the highest levels of phytoestrogens, plant-based compounds that can mimic estrogen. When these ingredients make their way into animal feed, they can also show up in the meat, milk, and eggs we eat. And just like PUFAs, these compounds accumulate over time, disrupt metabolic signaling and hormonal balance.

What are Phytoestrogens?

Phytoestrogens are plant estrogens. While they’re not identical to the body’s natural estrogens, they are close enough in structure to stimulate estrogen receptors in the body and disrupt hormonal balance (ref). This makes them endocrine disruptors (ref).

In fact, the term "phytoestrogen" originates from early observations of estrogenic effects in grazing animals and humans (ref).

We are exposed to these compounds now more than ever due to changes in our food system, which is negatively impacting hormonal balance and metabolic rate.

Alarmingly, phytoestrogens have much higher potency and our exposure is higher (ref). In fact, plasma phytoestrogen levels in soy-fed infants and vegetarians are orders of magnitude higher than levels of BPA or phthalates (ref).

So while the public focuses on plastics, the food supply may be an even more significant source of hormonal disruption.

Why do people say phytoestrogens are good for us and our hormones?

There’s a misconception that women need more estrogen as they age. This is not always (and rarely) true. But what many miss is that estrogen can be high in tissues, even when it appears low in blood (ref).

Estrogen dominance, not deficiency, is increasingly common, fueled by synthetic hormones, environmental estrogens, and yes, food.

The medical system has pushed synthetic estrogen for decades because it’s profitable. In fact, the global menopause market is projected to hit $24.4 billion by 2030 (ref). No wonder there’s an incentive to keep the “more estrogen” train going!

There’s also massive agriculture industry influence.

For instance, let’s analyze the Chief of Staff of the USDA for the last two presidential terms:

- Under 2025 Trump Administration = Kailee Tkacz Buller

- Under the previous Biden Administration = Julie Johnson

Julie Johnson served as President of the National Oilseed Processors Association (NOPA) and the Edible Oil Producers Association (EOPA) from 2015-2019.

Kailee Tkacz Buller served as President of NOPA and EOPA from 2019-2021.

NOPA represents the US soybean processing industry, and is involved in 'advocating for the benefits of vegetable oils' EOPA is a trade group that represents companies involved in the production of 'edible oils' (seed oils) like soybeans, corn, canola, and sunflower seeds, and plays a role in policy decisions affecting 'edible oil' production.

The soy industry (and Big Ag which profits immensely from soy industrial agriculture) has a huge financial stake in promoting soy as heart-healthy, hormone-balancing, and anti-cancer.

There might be short term benefits with phytoestrogens. In fact, most pro-soy, pro-phytoestrogen studies are short-term or epidemiological, and don’t track long-term effects.

But when you take a step back and consider total exposure (diet, livestock feed and the environment), the risks become clear. We are exposed to estrogen everywhere we turn!

Phytoestrogen intake warrants caution due to its potential negative effects on health. (ref, ref)

But What About the Japanese?

They eat a lot of soy and are fine, right?

Similar to other foods, we forget traditions.

Traditionally, Asian cultures consumed soy in small amounts and almost always in fermented forms like miso, tempeh, natto, soy sauce, and fermented bean pastes. These fermentation processes helped reduce anti-nutrients and lowers phytoestrogen levels (ref), making soy easier to digest and less hormonally active. Soy was used as a condiment or flavor enhancer, not as a main protein source, and it complemented animal-based foods rather than replacing them. This is a stark contrast to today’s heavy use of unfermented, processed soy products in Western diets.

Even so, did you know that breast cancer is the number one cancer in Japan? (ref) Since we know excess estrogen increases risk, could the extra phytoestrogen exposure be playing a role?

Those Sounding the Alarm

Many experts are now voicing serious concerns about the widespread exposure to phytoestrogens (ref, ref).

Here is a quote from a metabolism-focused doctor who treats cancer, Dr. Connealy:

"While flax’s phytoestrogens are not as immediately powerful as estrogens in medications like birth control or HRT, they can accumulate in the body over time and disrupt hormone balance. They act on estrogen receptors, interfere with the body’s natural estradiol metabolism, and increase the overall estrogenic burden, which directly contributes to cancer.

One of the biggest issues with flax is that it is often marketed as a “natural” or “balancing” estrogen source when, in reality, it adds to the estrogen load rather than truly balancing hormones."

Dr. Wendy Sellens is another example, a respected breast thermologist, sees dietary phytoestrogens as anything but benign. (ref)

Drawing on decades of thermography data, she and her mentor Dr. Hobbins have shown that:

-

- Phytoestrogens increase blood vessel activity in breast tissue, a marker for elevated cancer risk

-

- Phytoestrogens activate estrogen receptors and stimulate potentially dangerous tissue changes

-

- Patients showed breast vascularity changes within months of adding phytoestrogens to their diets

-

- She treats phytoestrogens as environmental hormone mimics, and sees improvements in breast imaging when phytoestrogens are reduced or removed from the diet

Her advice? Avoid them, especially if you have concerns about breast cancer, fertility, or estrogen dominance.

Concerning Research Findings

-

- High intake of phytoestrogens has been linked to hormonal abnormalities in women, men, and even children. (ref)

-

- A 2017 review explains that soy phytoestrogens (like genistein and daidzein) act similarly to synthetic endocrine-disrupting chemicals (like BPA), disrupting the neuroendocrine system by altering thyroid and sex hormone pathways, posing particular concern for infants, children, and sensitive individuals. (ref)

-

- A 2009 meta-analysis found that isoflavones from soy can lengthen the menstrual cycle and suppress key ovulatory hormones like luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). (ref)

-

- In a 2008 clinical case report, physicians treated three women (ages 35–56) experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial changes, and dysmenorrhea. Symptoms resolved after reducing soy intake, highlighting that high isoflavone consumption may negatively impact female reproductive health. (ref)

-

- Elevated urinary levels of genistein and daidzein have been associated with idiopathic infertility and reduced semen quality in Chinese men—and lower sperm morphology in U.S. men actively trying to conceive. (ref, ref)

-

- Early-life exposure to phytoestrogens has been shown to alter the development and structure of the female reproductive tract, contributing to increased infertility later in life. (ref)

-

- Thermographic imaging has revealed that high-phytoestrogen diets may worsen breast cancer outcomes by increasing vascular activity in breast tissue. (ref)

-

- A 2007 Cancer Research journal article concluded:

“There is very little human data on the role of phytoestrogens in preventing breast cancer recurrence… there is no compelling evidence that phytoestrogens help menopausal symptoms, and given potential concerns for stimulating breast cancer cell growth, it should not be recommended for use to treat these symptoms in post-menopausal women.” (ref)

This is especially critical when it comes to young children.

Exposure to estrogen-mimicking compounds during key developmental windows, especially in gestation and early infancy, can lead to a wide range of adverse outcomes, regardless of the animal model studied (ref). These include:

-

- Malformations of the ovary, uterus, mammary gland, and prostate

-

- Disrupted brain development

-

- Early onset of puberty

-

- Reduced fertility

-

- Increased risk of reproductive tract cancers

These findings align with concerning real-world trends: (ref)

Girls are entering puberty earlier.

Women are struggling more with fertility.

Sperm counts have declined by over 50%.

As one study put it:

“Consumption by infants and small children is of particular concern because their hormone-sensitive organs, including the brain and reproductive system, are still undergoing sexual differentiation and maturation. Thus, their susceptibility to the endocrine-disrupting activities of soya phytoestrogens may be especially high.” (ref)

Phytoestrogens & Metabolism

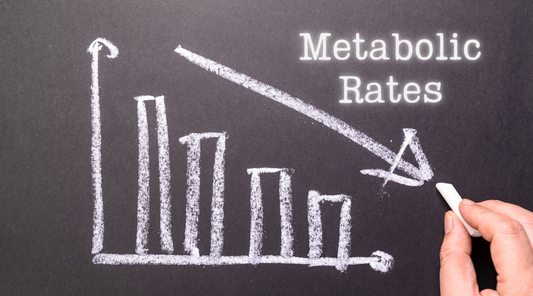

Unfortunately, phytoestrogens affect more than hormones. They activate PPAR alpha (ref), a nuclear receptor that regulates gene expression related to fat metabolism.

-

- PPARα activation shifts metabolism toward fat storage

-

- Chronic PPARα activity has been linked to metabolic downregulation and obesity

-

- One study showed obesity reversal in mice by suppressing PPARα target genes (ref)

-

- Other PPARα activators include phthalates and PFAS

Elevated estrogen levels increase thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) (ref, ref), a protein that binds to thyroid hormone (T3) and makes it unavailable to your cells. Since T3 is like the spark plug for your metabolism, essential for cellular energy production, this means less available T3, less energy, and a slower metabolic rate.

In short: Estrogen dominance → more TBG → less active T3 → slower metabolism → easier fat gain.

It’s no wonder estrogen is used in the livestock industry to fatten animals more efficiently.

Phytoestrogens don’t just mimic estrogen, they’ve also been shown to disrupt thyroid hormone transport in the blood (ref). Studies reveal that soy phytoestrogens can impair thyroid function in individuals with type 2 diabetes (ref) and even in healthy postmenopausal women (ref).

Where are Phytoestrogens Found?

The highest dietary sources include:

-

- Soy

-

- Flax

-

- Products made with soy or flax (like soy “dairy” or bread with flaxseeds)

But here’s what few are talking about:

Livestock feed.

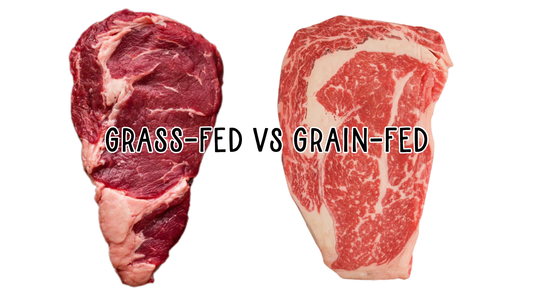

Soy and flax are common livestock feed ingredients, and phytoestrogens are transferred into the animal’s fat, milk, and eggs (ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref), increasing our dietary exposure.

Studies show:

-

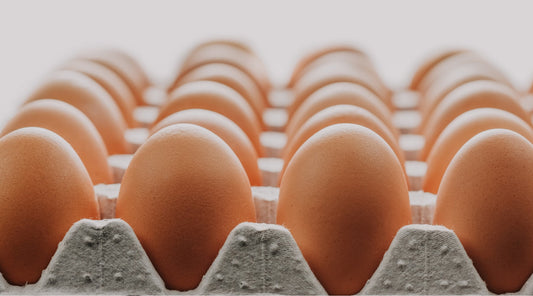

- Phytoestrogens in soy are absorbed and transferred to the tissues and eggs of chickens (ref)

-

- When chickens eat feed higher in phytoestrogens (for ex: isoflavones in soy or lignans in flax), the level of phytoestrogens in the egg yolk increases. (ref)

-

- “Defatted soybean meals… are often used as a protein source for feeding domestic animals and, therefore, considerable amounts of isoflavones are expected to be contained in animal products such as eggs and milk.” (ref)

-

- Eggs from flax-fed hens had 303% more phytoestrogens than controls (ref)

A study from Ohio State University (ref) found that the phytoestrogen content of eggs increases in direct proportion to the phytoestrogens in a hen’s diet, similar to the pattern seen with PUFAs. Among 18 commercial egg brands tested, isoflavone levels ranged from 330 to 1390 ng/g, with soy-fed hens producing eggs with significantly higher concentrations of these hormonally active compounds. The researchers concluded that eggs can be a notable source of dietary phytoestrogens depending on the feed used.

While the amount passed into meat and eggs may be lower than eating flax or soy directly, these foods are often consumed daily, making chronic, compounding exposure the real concern. And because some phytoestrogens are fat-soluble, they can accumulate in the body’s tissues over time, especially in fat-rich areas.

Another important factor is fiber.

Whole plant foods like flax and soy contain fiber, which can reduce phytoestrogen absorption to some extent. Insoluble fiber, in particular, can physically trap isoflavones and lignans in the gut, limiting their contact with absorptive surfaces and helping them pass through the digestive tract unabsorbed.

That doesn’t mean you should start loading up on soy and flax, please don’t.

But it does mean that when phytoestrogens show up in animal products like eggs, milk, or meat, they’re in a more absorbable form. Unlike fiber-rich plant foods, animal fats are low in fiber and rich in lipids, creating a matrix that promotes efficient uptake of these compounds.

In fact, research suggests that phytoestrogens from animal-derived foods (though lower in quantity) may have stronger biological effects because they exist in more estrogenically active forms.

When animals eat soy or flax, the phytoestrogens (like daidzein) are metabolized in their gut and converted into more potent compounds such as equol (ref). These pre-digested forms are then stored in the animal’s fat or eggs, ready for human consumption in a more bioavailable state.

“Isoflavones ingested as feeds are believed to be biologically transformed to their metabolites and sometimes accumulated in animals.” (ref)

So while the total amount of phytoestrogens in animal fat may be small, they can pack a stronger hormonal punch per gram for more sensitive individuals, especially without fiber to slow their absorption. An egg yolk, for example, is a lipid-rich, low-fiber delivery system, perfect for efficient human uptake.

The Good News

You can opt out of this endocrine mess.

Studies show soy- and flax-free diets produce eggs with no detectable phytoestrogens (ref).

This means we can reduce our phytoestrogen exposure by avoiding feeding them to livestock.

At Nourish Food Club we do just that.

-

- We do not feed soy, flax or other high phytoestrogen feed ingredients

-

- We don’t just guess, we test for phytoestrogens in our eggs

-

- Our results show virtually no phytoestrogens

Testing performed by Creative Proteomics, compared to values in the literature reported for chickens consuming soy and flax.

Eggs don’t need to be a phytoestrogen source. So let’s not make them one.

Maybe this is another reason why many of our customers can finally digest eggs again, since hormonal disruptions can cause systemic issues in the body.

Conclusion

We’re now exposed to more phytoestrogens than at any other point in history, and the long-term health effects remain largely unknown.

With hormonal imbalances on the rise, there’s more than enough evidence to justify caution. In a world loaded with PUFAs and estrogenic compounds, it’s no surprise that testosterone is dropping and metabolic dysfunction is becoming the norm.

Every small reduction in exposure matters, because these effects compound day after day, year after year.

Real food should support your health, not disrupt it.

And your internal environment is shaped not just by what you eat…

but by what your food eats.

So, if you could choose eggs without phytoestrogens…

Would you?

Because real food should support your hormones, not disrupt them.